Kim Rubenstein

I was a child when first told “patience is a virtue” — a phrase tagged to the 14th century English poet William Langland who wrote in Piers Plowman “patience is a fair virtue.” In my case it took a while for the message to sink in as I recall counting down the days before a flight to Israel during my law school student summer holidays.

Over the years, however, and perhaps amplified by the COVID experience, I have come to appreciate the wisdom of the phrase as with patience and persistence (timing too was a factor) I have completed professional projects that seemed like they were taking forever and would never be finished.

One was a citizenship law case with a very long lead up. In the meantime, I had honed my citizenship law expertise both as an academic and a practitioner. While teaching and researching, I have, nonetheless, maintained a Legal Practising Certificate and for 35 years I have been taking on cutting-edge citizenship law cases, largely pro bono, and advocating for individuals in the Courts.

Some things do happen quickly. My very first appearance was in the High Court in Brisbane opposed to the Commonwealth Solicitor General. After breaking to consider the requested leave to appeal, the two-member bench turned it down. My argument, however, won over the Solicitor General and he invited me to be his junior before the Full High Court in another citizenship case. Thereafter, it wasn’t long before I stood opposite him, in the same court, acting pro bono for another individual claiming Australian citizenship. So, my first three cases as counsel were all in the High Court, just like that. I tell the story because the virtue of patience is more keenly appreciated after those times when everything appears to come in a rush.

But thereafter, the waiting can become excruciating, and it is then that one must dip deep into the well of endurance ever reminding oneself to hold tight and true as patience is a virtue and not easily attained. In the citizenship case I referred to, all my patience was put to the test and much more so for my client. My lesson in the true meaning of patience began in this way. I was contacted by a person who had borrowed my book on Australian Citizenship Law from his local library, trying to navigate how to challenge his wife’s cancellation of her citizenship approval. She had been subjected to a truly dispiriting ordeal. While having received a formal letter congratulating her on the approval of her Australian citizenship application, she still needed to take the oath (or affirmation) at a ceremony, for the actual status of Australian citizen to be bestowed. Yet, before that oath was taken the Minister cancelled the approval. There had been a difference between the date of birth on her original documents and the later ones – all clearly explained by her in her application – but suddenly not believed by the Department.

There began a glacial journey to right that wrong. It took fifteen years. There were

‘Freedom of Information’ applications; the Ombudsman got involved; there were several merits review hearings in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal; and, not to mention, several Federal Court applications. The emotional and psychological toll on her and her husband was immense.

Patience is not always easy to maintain and particularly by those whose precious word is disputed. But through grace and perseverance, her third application for citizenship was finally granted and she became an Australian citizen. She was a person with no criminal convictions, who did years of valuable work in the care community and was of absolutely no danger to anyone whatsoever — indeed with a longer story to tell elsewhere — she is now a citizen, albeit 15 costly and painful years too late. Thankfully, though, patience and persistence finally won out. I felt like a marathon runner too when I attended her citizenship ceremony and experienced the greatest joy on witnessing her take the oath and become an Australian citizen. It clearly demonstrated to me that patience is a virtue.

My second example of this sage advice links to a different aspect of my citizenship work – not purely the legal status of who is and isn’t a citizen but how citizenship is exercised. How do we, as individuals, practice our membership and participation in the broader community? I describe this as ‘active citizenship’ and I developed one part of that work by meeting with and interviewing ‘trailblazing’ women lawyers. The National Library of Australia’s massive and ever-growing oral history collection now includes over fifty whole-of-life oral histories of women from a range of ages (from their 30s through to their 80s, indigenous, non-indigenous, migrants and multi-generational Australians, Catholic, Jewish and non-believing), all with law degrees and who have used the skills and experiences from their individual broader life experience, and their various forms of legal practice, to have an impact on others in society; as a form of active citizenship in the civic sphere more broadly.

In addition to their oral histories, the project also led to the development of an online exhibition that you can view. The 50 oral histories and biographies and information about these women are part of the exhibition. In addition, other trailblazing women lawyers nominated for interview but not interviewed due to the limits of the funding, wrote and reflected on their own experiences. These can be read in the Auto/Biography page. Indeed, there is much else to dip in and out of in the exhibition.

But this is where the patience aspect returns. Having established and launched the exhibition, the question arose, how do people come to know about the exhibition, especially as an educational tool to inspire young men and women to become active citizens themselves? Well, before COVID began, someone suggested raising funds to develop curriculum materials to assist teachers to enable students to use the exhibition as a resource for a range of educational purposes and to appreciate the fascinating stories of these women. Having then raised the funds it took me time to find someone to navigate the Australian curriculum framework (understanding that it is a task in itself!) to help develop the materials. Then, COVID set in, and a few years went by.

But patience and persistence meant that three years later, the links between the oral history project and the National Library of Australia’s existing online digital classroom ultimately landed, thanks to the timing, with the NLA launching curriculum materials for Year 10 students. The materials support the teaching of the ‘Building Modern Australia and The Globalising World’ part of the Australian curriculum. You can listen to me explaining the collection and I encourage you to share this far and wide! So, it is important to keep going, to stare through obstacles, to keep faith in the way ahead and to press on looking for a path and knowing that you will somehow find one.

Finally, in my set of three examples of patience and persistence (as I began thinking about this topic, I realised I have more, but one must draw a line ), I look to my interest in citizenship and Australia, and its multicultural history. As a 6th generation Australian descendant of Henry Cohen, a Jewish convict transported to Australia, my own history and experience as a Jewish Australian (or Australian Jew), has been a constant frame in my analysis of membership and community.

It may have been for that reason I was asked in early 2020 to interview Arnold Zable for the ANU/The Canberra Times Meet the Author Series on his recently released The Watermill. Eager to do so I was very disappointed when COVID lockdowns shut down the event. I was frustrated, as not having met Arnold, I was eager to find out more about his background and road to writing. While we were both involved in an online recorded conversation with Jaivet Ealom on his book Escape from Manus, it was only in March 2023 that we finally met in-person, at a minyan, sharing the sadness of the loss of our mutual friend Danielle Charak.

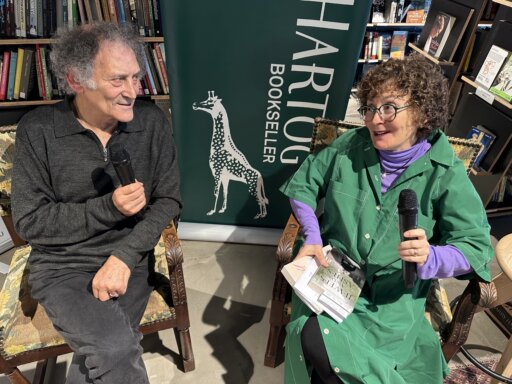

It was then three years since our planned interview session. With that meeting, knowing that Danielle would surely approve, we determined we would still like to do it — and there began the longer process of organising it. There were, of course, hurdles but we were patient and persevered. The interview finally happened at the ANU Harry Hartog bookshop over a year later.

And thanks to TJI you can watch that interview wherever you are and, if you are lucky, in the comfort of your homes. There are many themes I drew from Arnold’s books (the interview ranged over his extensive output between 1991 and 2020) drawing attention to the links and synergies and comparisons between Jewels and Ashes and The Watermill — with the cover of the most recent addition of Jewels having a striking connection to the cover of The Watermill.

In drilling down into the beautiful stories that are presented in The Watermill they remind me, as a person interested in the relationship between the citizen and the state, of the power of the State. My work is often motivated by protecting the individual, through law, from the abuse of State power. As Arnold writes, “Humans will always lose their way, come to their senses, and lose their way again. There will always be tyrants to be overthrown and tyrants plotting to replace them.” In the chapter ‘Republic of the Stateless’ I love the play on words – stateless people are without a national structure/governance – they have no protection – whereas the concept of the Republic – is one of governance – a Republic of Statelessness is a play on the state of statelessness. And the ongoing tragedy of Australia’s brutal immigration policy, from Federation forwards, which drives citizenship policy, is poignantly told throughout all of Arnold’s work, including the refugee stories, the stories centred on Indigenous Australia and the tragic Siev X sinking.

The title of our long-planned interview was promoted as Trauma and Healing, Memory and Forgetting: A conversation with Arnold Zable. Neither of us can quite remember how that title was devised, but I hope you agree after watching it, that our patience and persistence in ensuring it happened is of value to you too and, when projects seem to be taking forever and are seemingly out of reach and unrealisable, you too are coaxed to recall that helpful injunction from childhood — patience is a virtue!

Kim Rubenstein is a Professor in the Faculty of Business Government and Law at the University of Canberra. Consistent with the theme of this piece, she took 28 years to complete the biography of her school principal: The Vetting of Wisdom: Joan Montgomery & The Fight for PLC